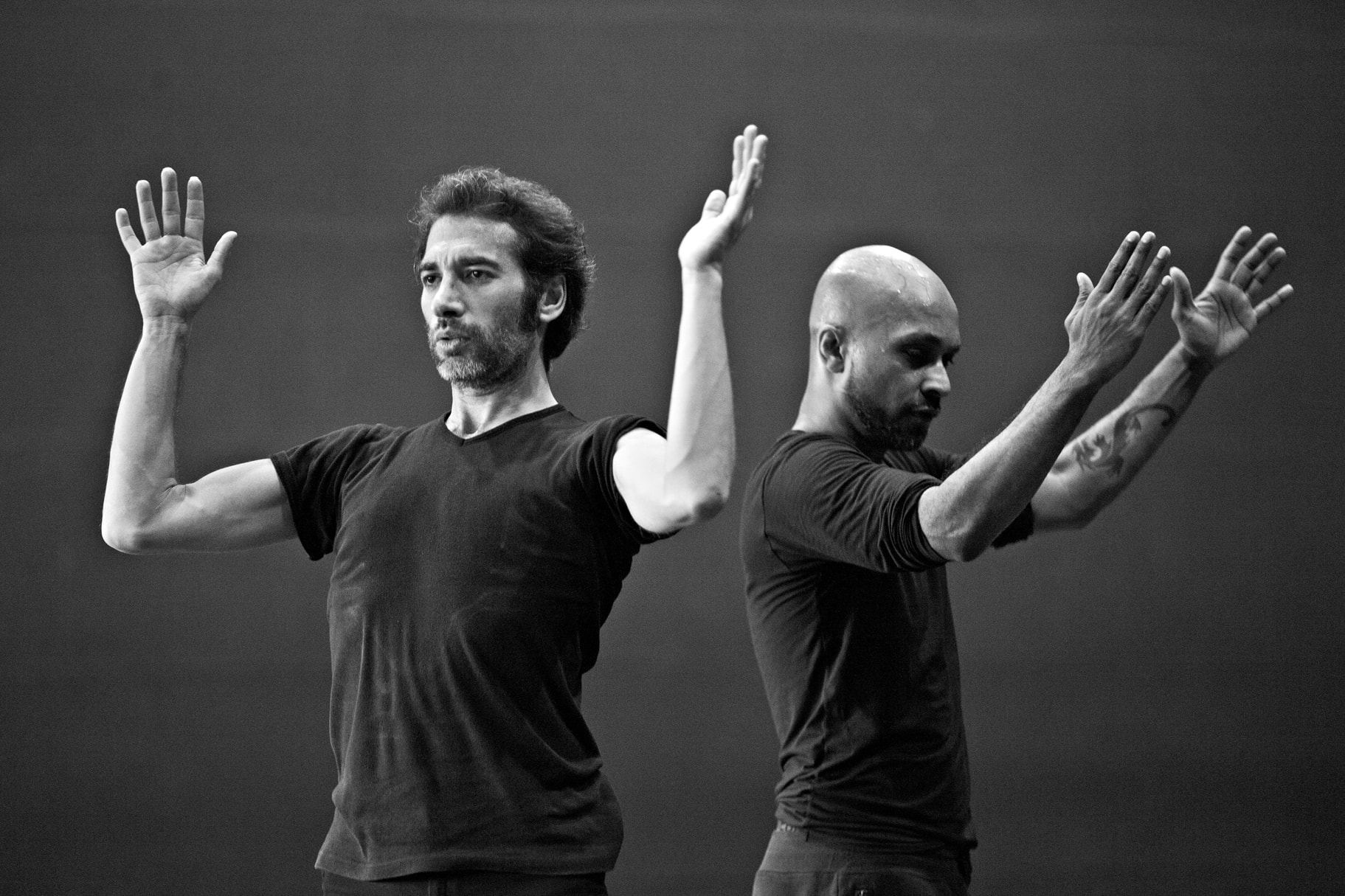

Akram Khan; Israel Galván; Khan; Galván; the very euphony of their names sets the scene. Dance before it became art. This transition, this intermediary space, this interstice is where they operate.

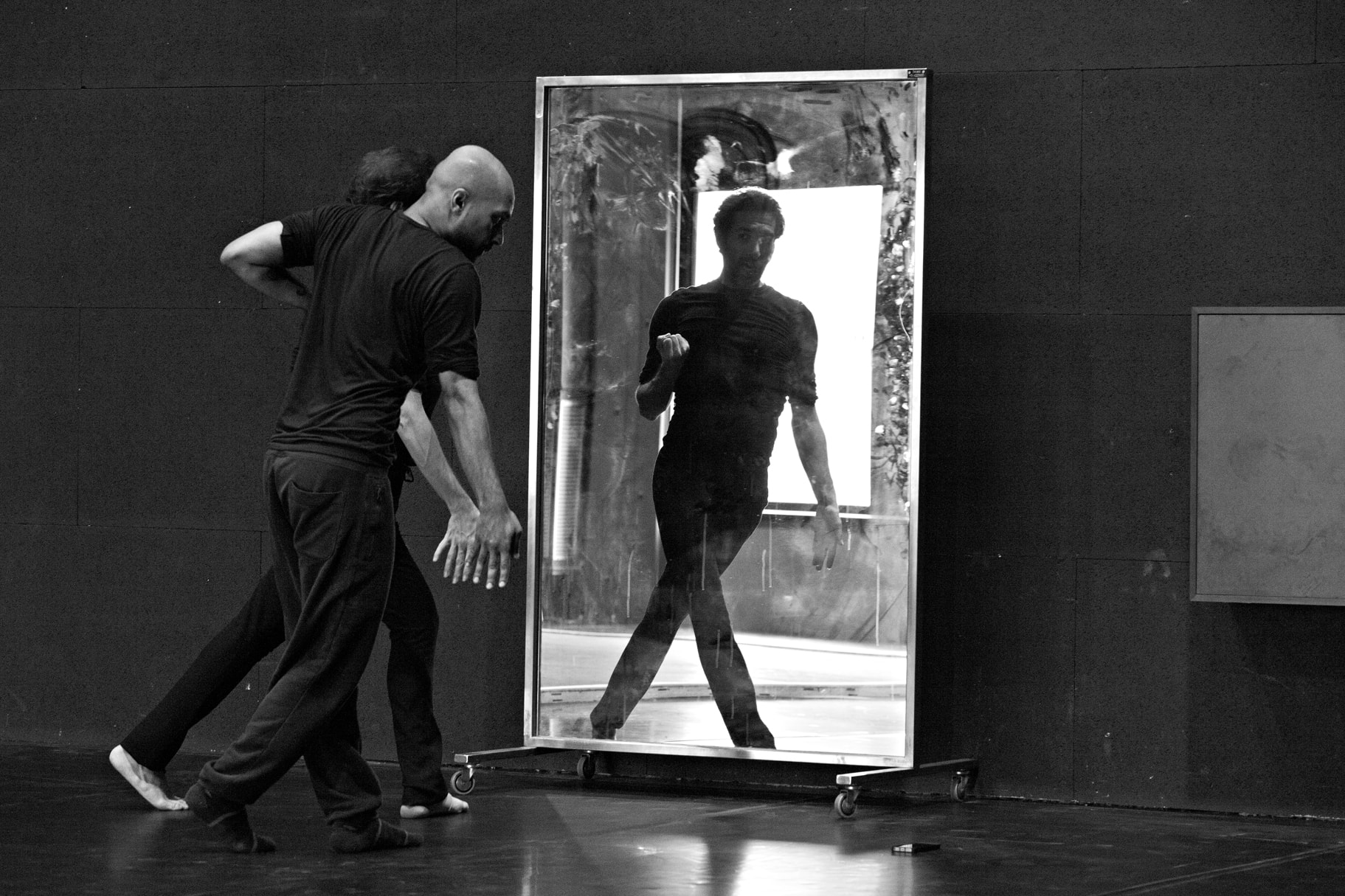

This is not, of course, an ethnic exchange between traditions, an exercise in global dance. It is about creating something from a way of understanding dance – derived, certainly, from dancing kathak and flamenco – that harks back to the origins of voice and of gesture, before they began to produce meaning. Mimesis rather than mimicry.

The hunter, lost in the countryside, imitates the gait of the animal he has come to hunt. Words are yet to be defined, guttural sounds which are understood almost as if they were orders, acts of command. Every part of the body is expressive, movements are read, they have a function. Torobaka!

Nor is there any need for primitivism. In one of the rehearsals Khan and Galván grappled with toto-vaca, a maori-inspired phonetic poem by Tristan Tzara. It was automatic. The bull (toro) and the cow (vaca), sacred animals in the dancers’ two traditions, but united, profaned (in the original sense of the word, to restore things to their common use), in an unconstrained dadaist poem.

Israel Galván and Akram Khan. This is what it is about, dancing without compromise and for the audience to go on perceiving it as art.

— Pedro G. Romero, January 2014